We used to have martinis on Monday evenings as consolation for beginning a new week, and again on Fridays, to celebrate having survived it.

Wednesday was Hump Day, the beginning of the much-craved slide toward the weekend. And the weekend, of course, was what it was all about.

I’ve been retired for more than a year now, and one of the strangest things to get used to is the absence of those markers. I no longer dread Mondays because they’re no different from Tuesdays. In fact, the sole day of the week that stands out now is Sunday—and that’s only because the New York Times shows up on my doorstep. (Side note: Martinis are still a twice-weekly event. At least.)

For the longest time, I looked forward to retirement. That’s what I was working for, I told myself. Along the way I imagined all the things I’d do when the time finally came—the new hobbies I’d start, the places I’d go. Half of my bucket list was designated for post-career activities. Most of all, though, I pictured retirement as the time when I would be free to write.

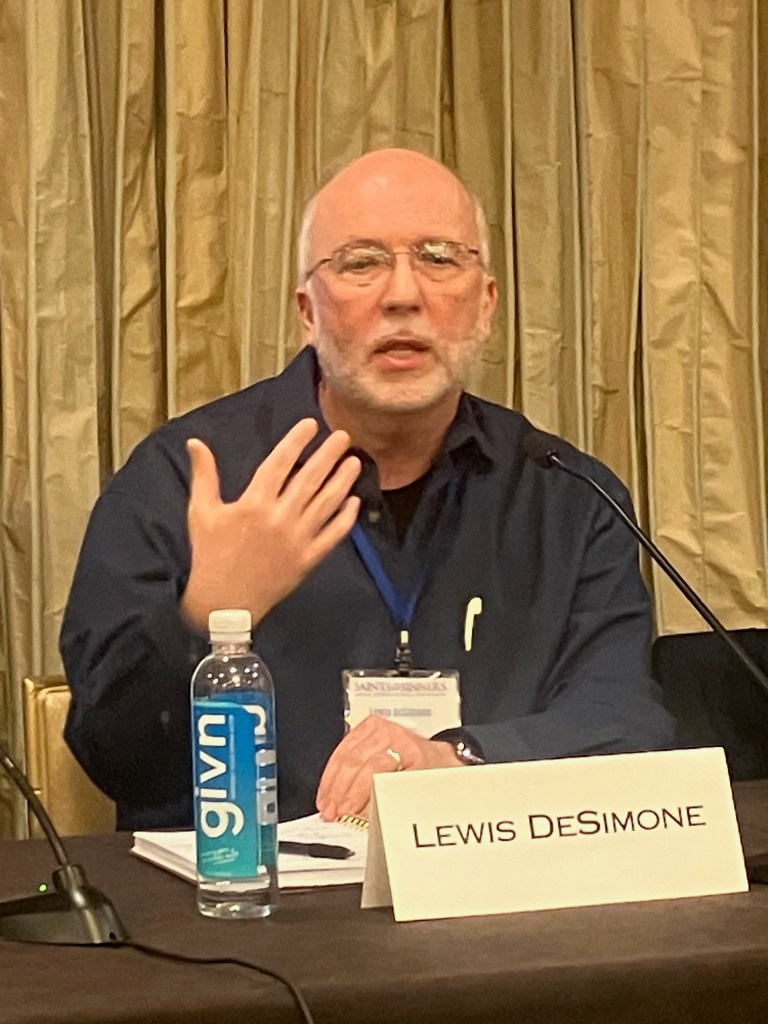

The most common question I get at readings is whether I have a ritual for writing. Everyone seems interested in how a writer squeezes in the time. The truth, for me, was that while I wanted to write every day—to be one of those mythical creatures who get up in early-morning darkness and dash off a few pages before heading to the office—when it came right down to it, there were too many other things going on. So I basically wrote my first few novels on Saturdays (which explains why so much time passed between publication dates).

Now that’s all changed. In theory, at least. I do write every day, if only for an hour or two. (The concept of being a “full-time” writer has never really appealed to me. Kafka was crazy enough with a day job; imagine if he’d sat alone in a studio for eight solid hours.)

Exit Wounds was written in less than a year—a record for me. It’s not spilling out the words I find difficult. The time-consuming part is revision. That’s where most of the work is, and frankly, most of the fun. The manuscript becomes a bit of a puzzle at that point, and my job is to rearrange the pieces, or add more, or cut some, until it all makes sense.

I once wanted a career as a writer, but over the years I’ve come to embrace writing as an avocation—if only because making a living at it isn’t in the cards for the vast majority of us scribes. And even in retirement, that’s what it is. I don’t want to think of writing as a “job”—that connotes drudgery. When writing stops being fun, it stops, period. Like my newer hobbies—gardening, wine tasting, bridge—writing has to be done for joy. Otherwise, I don’t have time for it.