My parents were into mid-century modern furniture without ever having heard the term. I suppose that’s because they bought it at mid-century, when it was just called furniture. When I was growing up, I thought it was nice but boring. But then I came out of the closet.

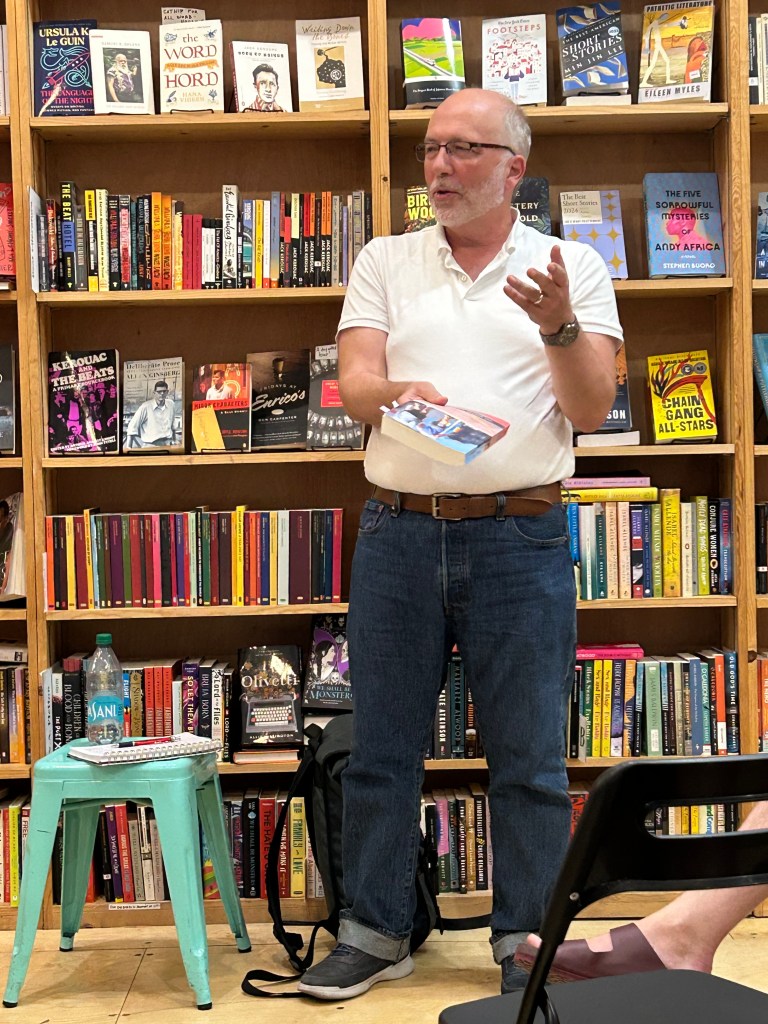

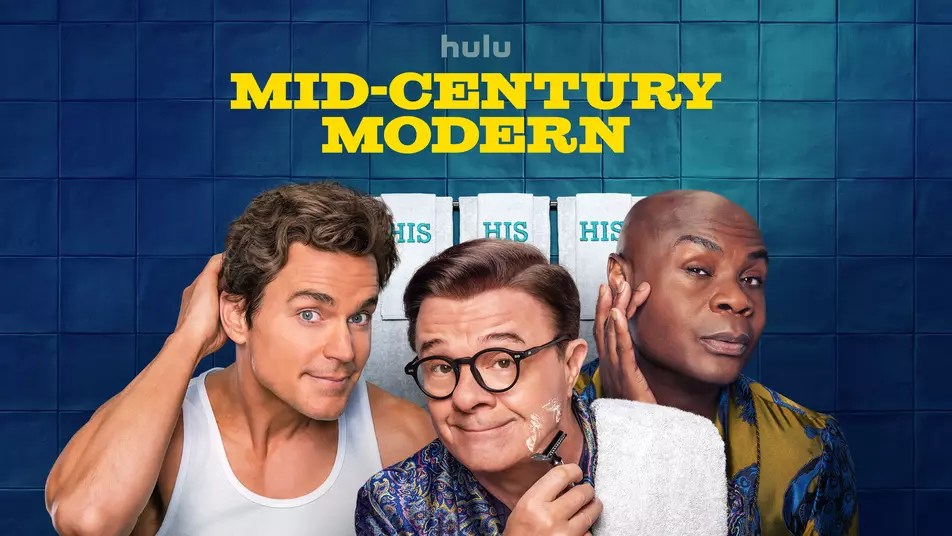

The style seems to be hotter—and gayer—now than when it started. It’s so hot and gay that it even has a sitcom named after it. Mid-Century Modern premiered on Hulu last weekend, coincidentally when I was at the Saints & Sinners Literary Festival to present at a panel on middle-aged homosexuals. (The actual title of the panel was “Generational Change in Gay Culture and Literature,” but that’s a mouthful.)

The show, brought to us by the same production team that created the groundbreaking Will & Grace, which, for me, defined “must-see TV” for a decade, stars Nathan Lane, Matt Bomer, and Nathan Lee Graham in a familiar formula—a group of friends living together in a created family that’s almost as dysfunctional as the home-grown variety.

Unlike its predecessor, a very urbane New York show, Mid-Century Modern takes place in Palm Springs. While Will & Grace’s characters were in their energetic and gorgeous thirties, this show focuses on an older set (which, interestingly enough, Will Truman would fit quite well in, at this point). It’s basically a cross between Will & Grace and The Golden Girls.

The very idea that Matt Bomer can be considered middle-aged boggles my mind. He’s actually more than 20 years younger than Nathan Lane, the oldest of the trio, but the chemistry among the three is strong enough for me to suspend my disbelief. If you squint, you can just buy into the conceit that they’ve been friends for thirty years (let’s forget that Bomer would have been underage).

Aside from the gay subject matter, Mid-Century Modern feels like an old-fashioned show, entertaining rather than didactic, its plots easily resolved in 30 minutes. It’s the kind of TV I crave these days, a relief from the chaos of the real world. It’s a delicious fantasy, where the perils of aging are deliberately glossed over. Even when the boys go out cruising, on a trip to Fire Island, there’s no sense of generational conflict. Arthur (Graham’s character) gets a little daddy attention, but the difference in age between him and his would-be suitor is barely acknowledged.

The setting, of course, has a lot to do with it. My own peer group (before we hit 40 ourselves) used to deride Palm Springs as the place where old homosexuals went to die. But even then we knew the city was both literally and metaphorically an oasis—where there’s water in the desert and civility in a hateful world.

That’s what San Francisco was for me, from the time I arrived in my early thirties to my reluctant departure 25 years later—a refuge from the harsher world outside. My novel Exit Wounds explores how the city, and the gay community that has enlivened it for so long, have changed over the years, as the distinctive qualities of both have begun to blend with the dominant world they once rejected.

Living the quiet life in Minneapolis, I’m in a holding pattern now, but I’ve often thought I might end up in Palm Springs, that hotter (at least on the thermometer) bubble. And now, after watching Matt and the Nathans, I find myself rethinking my aversion to desert weather. Being in a gay haven again, with people my own age, might just make up for it. Like my mother’s furniture, we were born in the mid-century era, and are now in the middle of our own century. We’re not done yet.

When my mother died a few years ago, we spent several days going through her things. There were lovely mementos, from jewelry to dishware to family photos. But there were also an inexplicable number of meat thermometers, for someone who rarely cooked more than scrambled eggs. More Hummel figurines than we knew what to do with. And so many never-used dish towels I wondered if she’d been expecting a flood.

We made the usual piles: keep, donate, throw. Most of her tchotchkes we laid out on a communal table in the building’s mail room. Every couple of hours, we’d come back with more stuff and find that her neighbors had already cleaned out the last batch.

I didn’t even think about the furniture, assuming the expense of shipping it 1,000 miles wouldn’t be worth it. And then my husband took one look at the mid-century modern bedroom set and insisted we take it. I’m so glad he did. That stuff is sturdy, still beautiful after 60 years and ready for more.