Many years ago, I was waiting for a friend in the lobby of the New York City Opera when a passing lady mistook me for the famous bass-baritone Samuel Ramey.

Well, actually, that’s not entirely true. The woman approached and told me I looked like Mr. Ramey. I shook my head with a flattered smile, and said she was mistaken. “No,” she said archly, “I didn’t think you were Samuel Ramey. I just said you looked like him.”

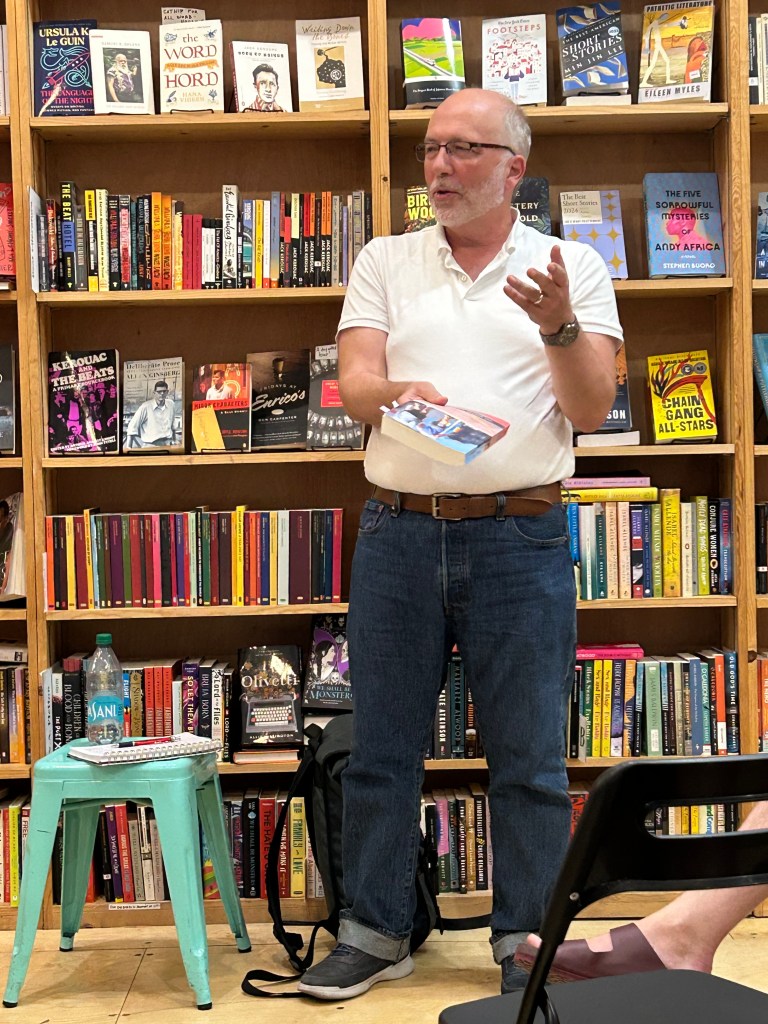

There’s a big difference between being someone and being similar to him. So, in that spirit, let me state clearly that I am not Craig Amundsen. I just play him in a book.

Craig is the first-person narrator of Exit Wounds, my recent novel. Like the book, he is a work of fiction. But try telling that to some of my readers:

“I love the scene where you dump your boyfriend.” (While I’ve dumped a boyfriend or two, it never happened the way it does in the book.)

“I felt so bad when you lost your job.” (I never worked in a bookstore, let alone was laid off from one.)

I suppose I should take it as a compliment. Perhaps the assumption that Craig is really me is evidence that he comes across as an authentic person and not just a cardboard cut-out. Nevertheless, there’s something creepy about being mistaken for an imaginary being.

These comments, of course, have so far come from friends, people who know me well enough to catch some of the true-to-life references in the book and to imagine me in the role of Craig or any of my other narrators. But I do have to wonder what other people think: Do all readers assume that a first-person narrator is a stand-in for the author? That Melville was in a shipwreck and floated to safety on a coffin? That Charlotte Brontë’s boss kept his wife in the attic? That Nabokov was a pedophile?

Every book has a narrator, of course; the third-person kind just gets to slide by unnoticed. It’s still a person, and may even be a character observing the story. It’s not always a god looking down as she manipulates her hapless characters. But if she communicates the story to you as an I, a personal bond is forged between narrator and reader (spoiler alert: this is often precisely what the writer is hoping for).

Perhaps contemporary readers are more likely to mistake the narrator for the author because of the dominance of memoir in the market these days. Readers are told to believe that everything in a memoir is factual (even dialogue and detailed memories from childhood), so they may have a Pavlovian reaction: if you see an I, then automatically believe what it says.

The truth is that no book is or can be a perfect representation of real life. No matter how much the story or character has in common with the author, nearly everything is modified in some way—for clarity, to elucidate a theme, or “to protect the innocent,” as they used to say on Dragnet. I would posit that this process is no less common in the highly problematic genre of memoir, but that’s a subject for another time.

It always seems to come down to the crucial difference between fact (what happened) and truth (what it means): writers should be primarily concerned with the latter. When necessary, we use fact to illustrate that truth—but still, everything is filtered through the imagination.

So yes, some of the events in my work are based on my own experience. Some of the characters’ personalities (narrator or not) are inspired by mine. Like Craig, I lived in the Castro for many years and served as a juror on a case much like his. But I never ran a bookstore, I didn’t go to Stanford, and I’m not from the Midwest. On the other hand, I’ve spent a lot of time in bookstores; I’ve visited Stanford; and I moved to Minnesota in my fifties. All those things helped me paint a picture of Craig’s life, but his lived experience is not mine. No more than Samuel Ramey’s marvelous voice.